In March 2020 CAST studio artist Nicola Bealing visited Mexico to initiate a residency exchange programme with the Centro de las Artes de San Agustín Etla (CaSa) in Oaxaca. After this initial visit she will also contribute to the development of the second phase of the project, which will bring an artist from Mexico to Cornwall. The project encourages artists from both countries to make relationships with museum collections in the areas they are visiting. In recent years Nicola Bealing has made paintings arising from her research in the archives of the Museum of Cornish Life in Helston and the Foundling Hospital in London. The visit to CaSa provided opportunities to explore Oaxaca’s diverse museum collections, while the artist visiting CAST will be supported to explore museum collections in Cornwall.

This is CAST’s first venture in hosting international residencies and we are very grateful for the generous support received from Art Fund to develop the exchange in partnership with CaSa.

Scratching the Surface (one month in Mexico)

by Nicola Bealing

I spent most of February and a part of March this year on a residency at the Centro de las Artes de San Agustín Etla (CaSa), in Oaxaca, Mexico. Leaving at the end of my stay, I just managed to squeak home before the world closed down in viral turmoil and the idea of travel completely imploded. Looking back at that bright, hot, colourful month now, from the deep sofa of eternal lockdown, it seems another world and another time away. I am incredulous and grateful in equal measure to have had this experience.

So now, to start at the end:

My last morning, leaving CaSa, impressions hurtle at me, oddly like the accelerated images of a silent film. For days I’d been followed by a muzzy cloud of ridiculous homesickness for this place I hadn’t yet left – but under this final navy-blue morning sky all was super sharp.

I hand my key for the last time to the stone-faced police guard sitting in the shade of his floral umbrella of bougainvillea – and receive, ha! for the first time, a smile in return. Then, past the church and across the square, where humming birds buzz the trees and a tiny boy tricycles around the pool, relentlessly pursued by his tiny, fat-legged sister: Matteo! Matteo!! MaTTEO!! Their mother sits on the kerb in the shade, chatting with the seller of popcorn and nieves: two colours, green or orange; two flavours, pistachio or melon (I’d been so confused, three weeks earlier to have my bag of popcorn doused with salsa).

Into the car which has seen many, many better days and off downhill through the village. Amiable dogs lie beside the road with absolute mathematical precision, measuring themselves with genetically inherited talent to just beyond the reach of wheels. Past the primary-coloured houses, painted with advertisements for food and ironmongery, and past the school where mothers hang on the railings and push lunches through to well-rounded children. Past the big church of joyous weddings. Maroon and white local taxis flit by, up and down in a constant stream. Just before the hut of Estetica Tomy Unisex beauty salon, an ox cart fills the road and we slow to its swaying pace.

Then this gentle hill road joins the main highway and the stampede of traffic to the city begins. Across the junction is ‘Funerales Nazareth’ where a wall painting of the man himself, Jesus, with the look of a used car salesman, stretches out his arms in welcome and invites inspection of the open-air display of coffins.

It is hot already and an intensely bright paint box of houses climbs the hills on both sides (Mexican hardware shops must surely have the best colour charts). At every traffic light beggars, squeegee merchants, sellers of bottled water and sunshades leap into action between the cars. A one-legged man has planted his wheelchair terrifyingly in the dead centre of the road, holding his hat for coins as the traffic swerves around him. A circus is setting up opposite the market, where lorries unload pineapples and mountains of coconuts spill out on to the road, iced white with dust. There is a purple fluff of jacaranda trees. On through the palisade fence of cacti (so exotic when I arrived) which lines the last stretch of the road to the smart but sweet airport – and I get the final glorious cliché of a pair of parrots flying from a tree before I turn and board for Mexico City.

But to go back to the beginning:

CaSa is housed in a complex that seems improbably grand for a nineteenth-century textile factory. Set high on a hill, the main building frowns down from the top of its steps like a Victorian headmaster. The mill was sited here in 1883 for the abundant water. Even now, nearly half of the water that feeds Oaxaca, the city 40-minutes-drive below, has first babbled through and out of CaSa’s hillside. Up here the village of San Agustín Etla, which expanded around the factory, sits greener, cooler and in a crisper air than the valley below.

The arts centre is a testament to the much loved and greatly mourned artist Francisco Toledo: an extraordinary man, who could dream a derelict factory into a place for learning, dialogue and international exchange. His vision was realised and completed in 2006 by architect Claudia López Morales, using an approach that preserves so much of the industrial nature of the complex and dabbles with water everywhere; it splashes over the cochineal-stained steps at the impressive facade of the building and lies, mirror-like, in flat basins skipped over by stepping stones.

Residency accommodation is in a long ochre terrace of cool, high-ceilinged rooms, fronted by a terrace with views to the hills. From the terrace I could spy down to where school groups solemnly toured the buildings or tourists wandered, shouting and selfie-ing, and watch as brides came for their formal wedding photographs, cushioned in sumptuous flounces and pillows of make-up, sometimes accessorised with their groom, but always with attendant best friend, beautician, lighting assistant, and serious professional photographer. A German arts collective arrived – and left, sweating gently in their black northern hemisphere coats.

CaSa was between exhibitions during my stay (‘Africamericanos’ had been programmed to open at the end of March, an examination of African heritage and influence in Latin America). The vast empty galleries were well used as rehearsal spaces by a changing group of international choreographers and dancers, their music echoing loud from the buildings.

Despite my best intentions, I never found time to use the production studio, laser cutter, Riso printer, animation, illustration or felt workshops, but hugely enjoyed mono-printing (and improving my vocabulary) with university students in the airy print room.

In the evenings there was quiet as the Centre closed to the public and the hills turned from brown to purple.

Nights were cool and often fiercely breezy, with a wind thumping against the door, billowing the curtain into my room. They seemed horrifically noisy at first, until I learnt the art of sleeping through like a baby. Dogs start barking as evening falls – holding complicated and heated conversations across the valley, from one village to the next. Long hours later, exhausted, but still keen to have the last word, they fall asleep one by one and there is a moment of the most beautiful silence. Then, almost instantly, still in darkness, the first cockerel crows, and triggers the call and refrain of every single cockerel across Mexico, backyard to backyard, hill to hill, coast to coast, continent to continent.

Light eventually follows and then, louder than the loud birdsong, the relentlessly cheery voice of the village loudspeaker starts. The day’s announcements – births, marriages, deaths and shopping bargains – are broadcast for all to hear, and sometimes the mobile tortilla seller joins in in competition as he drives up and down the streets, loud-hailing as he goes. 7am, time to get up.

Days fall into a rhythm. Food is oddly tricky. I learn that in Mexico lunch is between 2 and 5pm: arriving to eat, keen and hungry at 12.30, it is assumed you have come for breakfast. The eating places in the village serve bean soups, tortillas and stews of unapologetically large hunks of untamed meat, but most close at 5pm as family trumps tourism. However, I work out that with a well-timed tour of several of the miscelánea (one-roomed general stores with mysterious opening hours), I can buy most of life’s necessities: bread, oranges, chillies, beer and 1,000 types of biscuit.

I am embarrassed by my lack of Spanish and, although it does improve over the weeks, I find I do a lot of smiling, beaming inanely in an attempt to make up for my failings – and am met, sweetly, by much smiling in return.

On Sundays, a small market sets up among the eucalyptus trees above CaSa and there is bustle and chatter, wonderful fruit, juice, bread, quesadillas and a traditional sweetish drink, Tejate, sold in red and blue painted gourd bowls. A team of roller-skaters queue to buy carved mangoes, held on sticks like giant golden lollipops.

Down in Oaxaca food is everywhere: restaurants, taco sellers, cooked maize stalls, sellers of neon drinks and sweets and mezcal bars line the grid of colourful streets that forms the ‘cultural quarter’ –centred around the glowing church of Santo Domingo, and the Zocalo.

Stalls and street sellers display every bright and colourful thing that tourists might like, punctuated with blind buskers and dusty child beggars. Gangs of American and Canadian visitors of a certain age roam, bickering gently in artistic linen and face masks.

Oaxaca is generous with museums. I found favourites: the beautiful Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca with its baffling maze of vaulted galleries and fountain set in a former convent and the Rufino Tamayo Mexican Pre-Hispanic Museum – where artefacts are cheerfully displayed in rooms of the brightest Mexican pink or green or mauve and grouped, with humour, by aesthetic associations, rather than strict chronology or region.

Beyond this immediate ‘cultural’ centre, I criss-cross the city to visit artists in their studios and homes. There is impromptu, haunting flamenco in the secret garden/studio of Guillermo Olguín. José Ángel shows me gesso panel paintings and celestial works on paper. Ana Hernández collaborates with women from her home town to preserve vanishing techniques of embroidery and textile work. She also makes tactile sculptural objects – gleaming golden pumpkins and cast agave leaves. They share a home with a placid free-range rabbit and perpetually grinning dog. Santíago Rojo’s paintings examine the boundaries of encroaching urban development through the increasingly prevalent aerial viewpoint. He, Julio Barrita and Victor García are part of Cordoba Lab, a redundant meat cold store, now a space for production, exhibition and a platform for exchange of ideas – a hub for passionate dialogue around contemporary art in Oaxaca.

Before my residency I’d held conversations with myself and concluded that there was no pressure or likelihood of making much meaningful work in one short month in a strange studio. Instead, I saw myself as a big, amorphous sponge, mopping up all before me and going home to wring myself out and pick over the squeezings at leisure. But, predictably, with paint and brushes in my luggage and a generous space in which to work, doing nothing was no option.

The light and heat and colour of Oaxaca are dialled to maximum – almost painfully dazzling to eyes squinting from an English February. And, to add to the contrast, it is impossible not to notice that there are bright flowers everywhere. They escape in flurries over the walls of village gardens, glow vividly on roadside weeds and against the sky in leafless trees. Telling myself I simply needed to get them out of my system, before graduating to ‘real’ work, I begin to make paintings of plants and flowers in and around CaSa. Working in poster-flat, unforgiving gouache I record them deadpan, a series of straightforward portraits of daily encounters. These paintings slowly accumulate in a crisp heap in my studio, where they come to form a diary, a journal chronicling my time and wanderings in Oaxaca. Each of the images now holds the power to take me back with whiplash suddenness to precise moments and days. And of course, somehow the ‘real work’ never happens.

In 1924 DH Lawrence wrote of his time in Mexico:

One says Mexico: one means, after all, one little town away South in the Republic, and in this little town, one rather crumbly adobe house built around two sides of a garden patio: and of this house, one spot on the deep, shady veranda facing inwards to the trees, where there are an onyx table and three rocking-chairs and one little wooden chair, a pot with carnations, and a person with a pen. We talk so grandly, in capital letters of Morning in Mexico. All it amounts to is one little individual looking at a bit of sky and trees, then looking down at the page of his exercise book.

from Mornings in Mexico, first published in 1927

To pronounce grandly (as I do) ‘ I went to Mexico’, gives me a flinch of embarrassment; it claims too much for that glorious month when I was one little individual looking at a bit of sky and trees – and other things that came into view, but, in the end, barely scratching the surface of the country.

I’m conscious of all the stones I left un-turned and the issues I delicately side-stepped: of politics, protest, poverty, the Zapotec heritage and all those birds whose names I never learnt. I don’t know how best to answer or apologise for this – except to hope to return.

With thanks to CAST, Art Fund, Laureana Toledo and Daniel Brena.

Paintings:

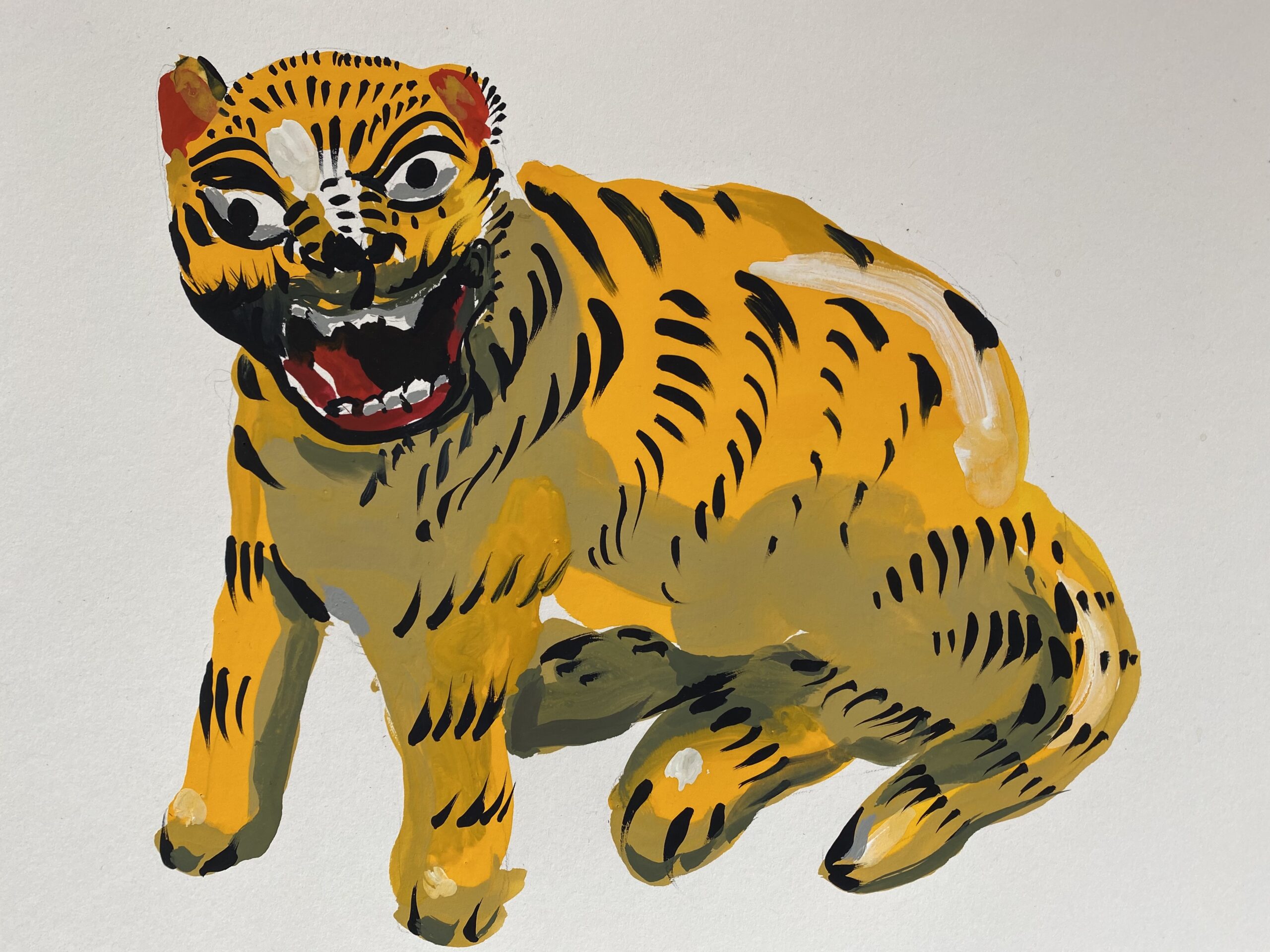

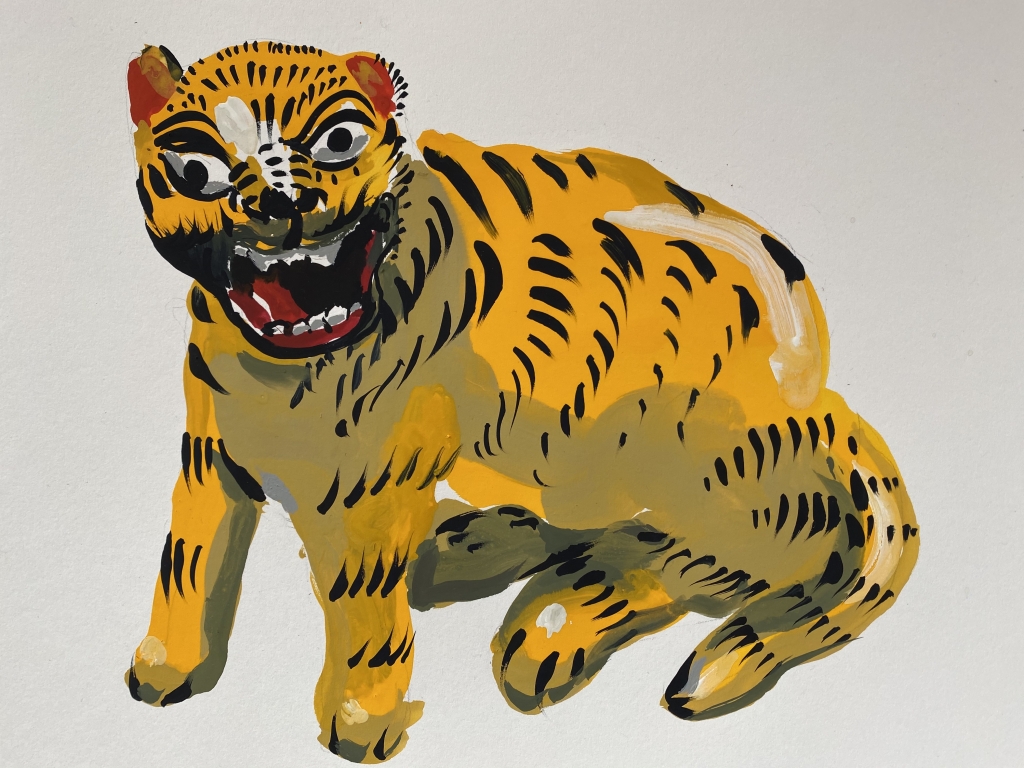

Wooden toy tiger from the Museo del Arte Popular, Mexico City (2020, gouache, 20x30cm)

Mexico diary 6: roadside amaryllis, San Agustin (2020, gouache, 50x32cm)

Mexico diary 11: cactus with orange string, coast road (2020, gouache, 50x32cm)

All painting images courtesy of the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London